Supreme Court immigration ruling: Due process in theory, deportation in practice

- Share via

- The court said those facing deportation had the right to challenge their removal, but advocates say the court made the process difficult.

- The court did not decide a larger issue: whether the Trump administration’s use of the Alien Enemies Act is constitutional.

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court’s ruling allowing the Trump administration to continue deporting immigrants under an 18th century wartime law was hailed as a victory by both the federal government and those challenging the deportations.

The high court left many questions about the law unanswered, experts said, which explains, in part, the contradictory reactions to Monday night’s ruling.

The divided court agreed the Trump administration can use the Alien Enemies Act to deport alleged members of a foreign gang, as long as they are given the right to challenge the government’s claim.

The decision is a victory for Trump and setback for federal judges who sought to check the check the president’s power.

“The critical point of this ruling is that the Supreme Court said individuals must be given due process to challenge their removal under the Alien Enemies Act,” Lee Gelernt, deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Immigrants’ Rights Project, who is leading the lawsuit, wrote in a statement. “That is an important victory.”

President Trump, writing on his social media platform Truth Social, focused on the other key part of the court’s ruling: “The Supreme Court has upheld the Rule of Law in our Nation by allowing a President, whoever that may be, to be able to secure our Borders, and protect our families and our Country, itself. A GREAT DAY FOR JUSTICE IN AMERICA!”

The ruling upends the orders of district court and appellate judges who had paused the deportations and said the administration had overstepped its power.

The court did not decide a larger issue: whether the administration’s use of the Alien Enemies Act is constitutional.

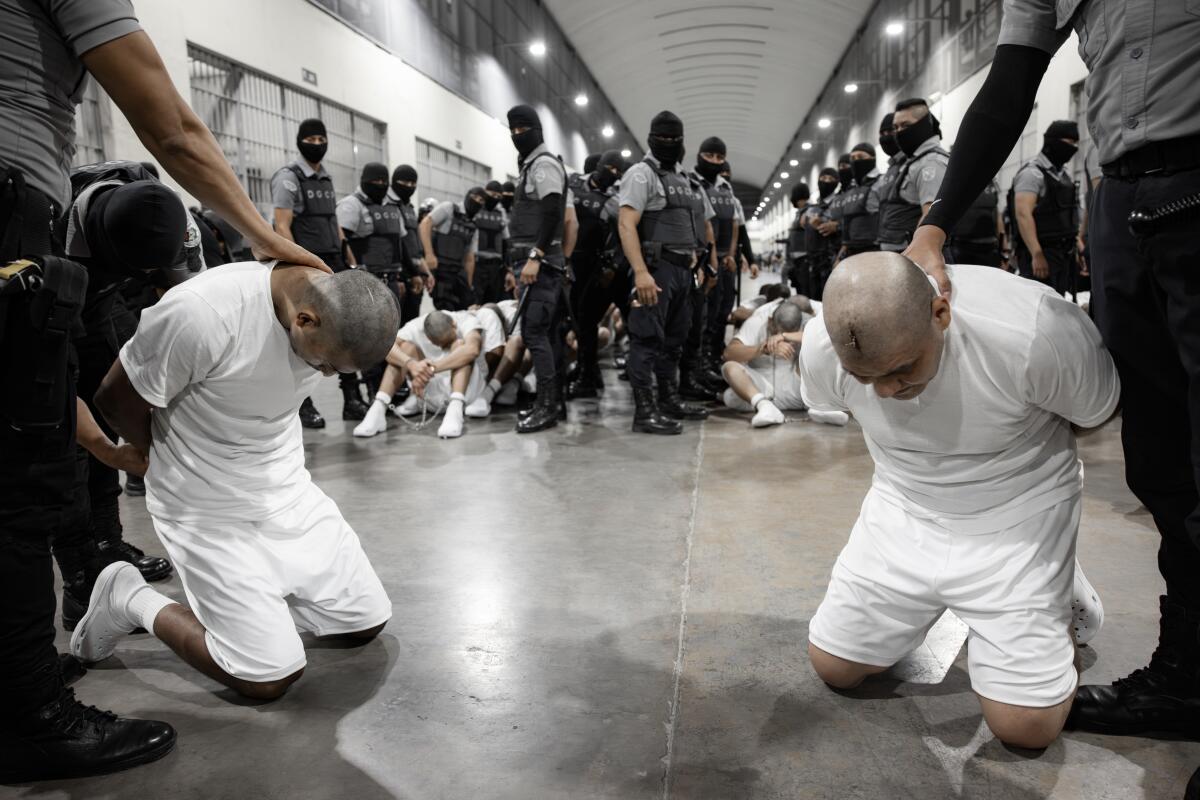

The families of many people deported under the law said they are not gang members. More than 100 men accused of belonging to the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua were sent to a maximum-security prison in El Salvador.

Though the court held that detainees have the right to challenge their removal, immigrant advocates said this comes with a catch: People held for deportation will have to file individual petitions in the district where they are detained, a difficult process for someone arrested in, say, California but held in Texas, far from family and lawyers.

Immigration officials sent many detainees to Texas before their deportation to El Salvador.

On Tuesday, the ACLU and other plaintiffs filed an emergency lawsuit in New York federal court to again halt removals under the Alien Enemies Act for people within that court’s jurisdiction.

Sen. Alex Padilla (D-Calif.) and three other Democratic members of the Senate and House judiciary committees issued a statement Tuesday saying the Supreme Court ruling will “will unquestionably harm people caught up in this oppressive nightmare.”

“Although the Court unanimously agreed that deportations without due process are illegal, the reality is the Trump Administration has been rapidly and erroneously deporting people, and has taken the position that those erroneously deported may be confined to foreign prisons with no redress,” the legislators wrote. “The Court’s requirement that challenges occur through individual habeas petitions will make it very difficult for people to successfully challenge their removals before they happen.”

The Alien Enemies Act was last used during World War II and, according to an overview from the National Archives, was employed to detain more than 31,000 people from Japan, Germany and Italy. Three times as many people of Japanese descent, mostly American citizens, were held at incarceration camps.

Former President Trump says that if reelected, he will initiate the largest mass deportation of undocumented immigrants in history. Experts say that’s unlikely.

Experts including Tom Jawetz, a former senior attorney at the Homeland Security Department under the Biden administration, are skeptical that immigrants targeted under the wartime law will actually be given enough time to find lawyers and challenge their deportations.

“While the court did provide sort of a mixed win, I think there is very good reason to be concerned that the process afforded to these individuals is going to be lacking,” he said. “With an administration that shoots first and really doesn’t ask questions ever, I think we’re going to see a lot more mistakes taking place through these kinds of removals.”

Lindsay Toczylowski, co-founder and chief executive of the Los Angeles-based Immigrant Defenders Law Center, represents a gay makeup artist who was seeking asylum when the Trump administration deported him to the Salvadoran prison. Officials cited his crown tattoos as evidence of him being a member of Tren de Aragua.

Toczylowski said the due process review required by the Supreme Court will be a disaster in practice.

“Most people forcibly sent to El Salvador were unrepresented,” she wrote on X. Referring to their detention in Texas, she added, “Trump purposefully moved them to remote detention centers in TX pre-rendition.”

Once these cases begin weaving their way through the court system and one makes it to the Supreme Court, the public will pretty quickly see what the court really thinks about use of the wartime law, said Gabriel “Jack” Chin, a professor who studies the intersection of criminal and immigration law at UC Berkeley.

“I’m not worried yet,” he said.

Jawetz said many questions remain to be answered by the Supreme Court, among them: What happens to those already deported under the Alien Enemies Act? Can this wartime authority be invoked during a time of peace and against a nongovernmental entity?

With the deportation pause lifted, those questions could now work their way through the court system in a much more rushed and chaotic fashion, Jawetz said.

In a separate decision Monday, the Supreme Court paused a lower court’s order requiring the Trump administration to return a Maryland man who Trump administration lawyers admitted was wrongly deported to the El Salvador prison.

Trump officials wrongly sent Maryland man to El Salvador but refuse to bring him back.

Such court-ordered returns are somewhat rare but have taken place. The administration has said it has no way to bring back the man, Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who was not deported under the Alien Enemies Act.

If the justices decide that the Trump administration cannot be required to bring Abrego Garcia back to the U.S., “there’s very limited hope that the courts will step in and say any of these folks who have been sent to rot in the Salvadoran prison have a chance of getting their day in court,” Jawetz said.